If your exceptions aren't exceptions but expectations, you're doing it wrong. Here's an example what programmers tend to do:

def validate_status(user)

case user.status

when 'active' then return user

when 'inactive' then fail InactiveUserError

when 'invalid' then fail InvalidUserError

when 'deleted' then fail DeletedUserError

else

fail UnknownUserStatusError

end

end

begin

validate_status(user)

rescue InactiveUserError

# do something

rescue InvalidUserError

# do something else

rescue DeletedUserError

# do something else 2

rescue UnknownUserStatusError

# do something else 3

end

I've seen also few cases, when exceptions parameters were used to pass objects that the programmer was later on working with!

As you can see, the whole flow of this piece of code is handled with exceptions. In this post I will focus on a performance reason why it is bad, (but if you're interested in how to refactor code like this, at the end of this post you will find some external links about that. That's why I've prepared a simple benchmark

require 'benchmark'

elements = [0, 1]

big_ar = (1..10000).to_a

TIMES = 100000

Benchmark.bmbm do |x|

x.report('break') do

TIMES.times do

elements.each do |i|

break

end

end

end

x.report('catch throw') do

TIMES.times do

catch(:benchmarking) do

elements.each do |i|

throw(:benchmarking)

end

end

end

end

x.report('catch throw heavy') do

TIMES.times do

catch(:benchmarking) do

elements.each do |i|

throw(:benchmarking, big_ar)

end

end

end

end

x.report('fail') do

TIMES.times do

begin

elements.each do |i|

fail StandardError

end

rescue

end

end

end

x.report('fail heavy') do

TIMES.times do

begin

elements.each do |i|

fail StandardError, big_ar, {}

end

rescue

end

end

end

x.report('raise') do

TIMES.times do

begin

elements.each do |i|

raise StandardError

end

rescue

end

end

end

x.report('raise heavy') do

TIMES.times do

begin

elements.each do |i|

raise StandardError, big_ar, {}

end

rescue

end

end

end

end

ruby benchmark.rb

user system total real

break 0.040000 0.000000 0.040000 ( 0.040243)

catch throw 0.080000 0.000000 0.080000 ( 0.082100)

catch throw heavy 0.080000 0.000000 0.080000 ( 0.082422)

fail 0.300000 0.000000 0.300000 ( 0.298863)

fail heavy 0.470000 0.000000 0.470000 ( 0.476829)

raise 0.300000 0.000000 0.300000 ( 0.305635)

raise heavy 0.480000 0.000000 0.480000 ( 0.475377)

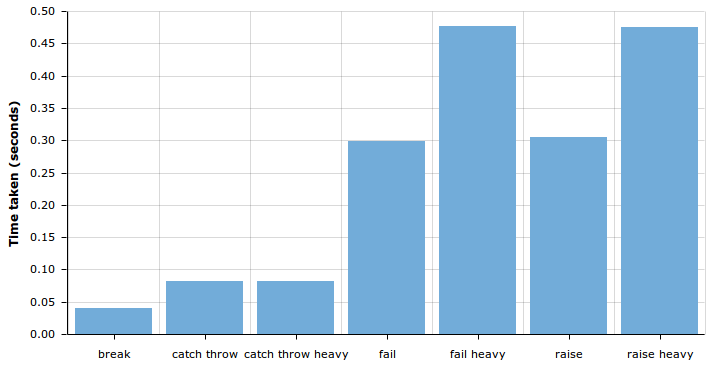

And this is how it looks on a chart:

Based on this benchmark we can see following things:

- Catch/throw performance is not influenced by the size of passed attribute - it doesn't matter if we pass a huge structure or a simple object

- Performance of fail and raise is almost equal, for both normal and heavy case

- Fail/raise can be up to 12 times slower than break

- Fail/raise can be up to 6 times slower than catch/throw

So, from the performance point of view, handling flow with exceptions can be much more expensive than in other ways. Exceptions are heavy because they are exceptions. They aren't suppose to happen all the time, that's why the implementers of compilers nor the designers of the language focus on their performance.

Refactoring

If you've noticed code like this in your apps, here are some great blog posts on how to fix that: